|

| Restored marsh area. |

Despite what Starbucks is trying to tell you, fall doesn’t officially start in the Northern Hemisphere until September 22nd at 10:29 pm (equinox party anyone?). And yet I felt now might be a great time to reflect on the summer. At this point, if you’re a semi-regular reader you probably know a bit about my interests, but today I want to share a peek inside my summer work. It was fun, it was muddy, and it was also just a ton of work!

|

| I'm just for scale, look at the height on that hybrid Spartina! |

But before I can really tell you what I did, I need to tell you why I did it. As a PhD student, I’m nurturing a little research agenda that I hope will mature over time. Right now, it’s at that horrible tween stage where it wants to be a grown up research agenda, but I keep driving it to the mall and embarrassing it in front of its friends. Regardless, when people ask about my work at parties or family functions, I tell them I study the impacts of invasive plants in tidal wetlands. Tidal wetlands are hugely important in terms of impacts to biodiversity (nursery habitat for many organisms) and ecosystem services (carbon storage, flood abatement, water filtration, and the list goes on…). Ironically, in California, only about 10% of our historic tidal wetland area remains, and to add insult to injury wetlands are one of the ecosystem most impacted by invasion.

But, why invasive plants? Plants are primary producers, hanging out at the base of the food web, and when they change, other things change in really interesting ways. My master’s research focused on the impacts of an invasive plant on songbird food webs. I found the plant impacted the insects, which the birds ate, thus impacting the birds. I was intrigued! That’s how I knew a PhD was right for me, after my MS, I have about 1,000 more questions. In my current research, I try to understand: How do changes in invasive plant density impact the effects these plants have on ecosystems? How does restoration approach impact ecosystem recovery after the removal of an invasive plant? How does understanding the function of invaders in ecosystems impact management choices? I have approximately a billion other small questions that I try to address, but those are the biggies.

Now, what does a work day in the life of someone trying to answer these questions look like? For about 6 months out of the year, it looks like me sitting at my desk, at my computer. But during the field season, especially the summer, things are very different.

Studying Restoration in the Low Marsh

|

| Restoration site types: Native Spartina foliosa (top left), actively replanted (top right), passive eradication (bottom left), invasive hybrid Spartina (bottom right). |

Tidal marsh plant communities are structured largely based on environmental stresses associated with inundation by the daily tides. When I’m working at my restoration sites, I’m down in the lowest elevations where plants persist. That means I need to be in the marsh, ready to work when the tide is low enough. Each field day, I rise at least two hours before the low tide level I need to get my business accomplished. Most of the time this summer, that meant being up at 4 am. I’ll admit it, it was a bit of a drag being up that long before the sun. I would change into my field clothes, make some coffee (so necessary), grab the lunch that I (hopefully) pre-made the night before, and head out the door. I jumped in my car, which is (again, hopefully) pre-packed with all the gear I’ll need for the day, and swing out of my parking lot to pick up my employee and potentially a few volunteers. Once we are all loaded up, we start the hour and a half drive out to one of my six sites in the San Francisco Bay Area. These awesome people are really what makes all my work possible, so if they fall asleep approximately 20 minutes into the drive, I focus on NPR and coffee.

|

| Two all star members of the wetland field crew! |

Once we arrive, we pull on our waders and prepare to get muddy. For this restoration work, I’m very interested in how invertebrates living in the soil are impacted by the different restoration approaches, specifically active replanting of native plants versus just eradicating the invasive and letting things passively progress. So, I take a lot of soil cores. Soil cores for grain size, soil cores for water content, soil cores for inveterate identification, soil cores for benthic algae analysis. So. Much. Mud. I also get to play with adorable crabs and watch the sun rise up over the bay. In the end, it’s always worth the early wake up call. Depending on the site and the day, the tidal window could be open for 4-7 hours. As the sea creeps back up toward the land and my transects, we pack up our gear and lug 30 pound buckets of mud back to my car.

|

| Muddy gear ready to be rinsed. |

*Cue very obnoxious pop music and more coffee to make it through the drive home*

What happens back at the lab that evening really depends on the time of day and what the plans are for the next day. Generally, we spray off all our gear (salt water = gear death), preserve and store all the samples we took, and go take showers. Lather, rinse, repeat for about 20 days spread out over 1.5 months.

Studying Management in the High Marsh

My other experiment this summer examined how different densities of an invasive plant might have different impacts to the ecosystem. This plant, (Lepidium latifolium, or white top) can occur in several different elevations in the marsh, but my master’s work showed the largest impacts were in the high marsh zone. Thus, I’ve concentrated my current work in that area. So, unless the tide is really high during the middle of the day, I’m generally not very tidally restricted for this work. I’m super interested in the impacts of invasive plants at different densities because we generally know about what things are like when these invaders are absent and when they are really bumping. That middle stage? A bit foggy. That’s where I come in, or so I hope.

|

| Marsh full of Lepidium. |

On Lepidium mornings, I wake up at 6 am, which feels like a luxury, let me tell you. I make coffee, grab my lunch, and head out to pick up my helpers for the day. Once we arrive at the field site, we set to work counting stems. I’m attempting to hold stem density constant between the different treatments, so a lot of this summer was spent driving out to the site and clipping out any extra stems that had sprouted up from the time of my last visit. These little suckers resprouted so aggressively! I learned a lot about how often I need to actually do this reclipping. I piloted this experiment this summer, so I didn’t take all those lovely soil cores in this case. I’m stoked for this February when I expand this project to three sites and really go for it!

___________________

|

| Crab lovin'. |

When I look back over this summary and compare it to my feelings after my first field season in the winter, I know I’m starting to make progress down my research path. In all honesty, during the winter I was simply trying to keep my life together. This time around, I felt I could breathe more easily, reflect more often, and make much better decisions over all. I also felt like this summer I actually have a lot of fun in the field! Sure, logistics are still difficult, and I definitely have a metric ton of mud still in the lab fridge to work through this week. Overall though, I feel like I can say things went well!

For those of you who are getting ready to start this graduate school journey, just remember that no one has it all together. Anyone who pretends that they do is absolutely full of it. This is a learning process, and learning is way scary! Talk to people you trust, take breaks when you need to, and remember why you signed up for this in the first place (cause you totally volunteered, btw)! Trust me; it’s always confusing, but navigating that confusion will become much more of a fun adventure!

Until next time! If you need me, I’ll probably be in the lab.

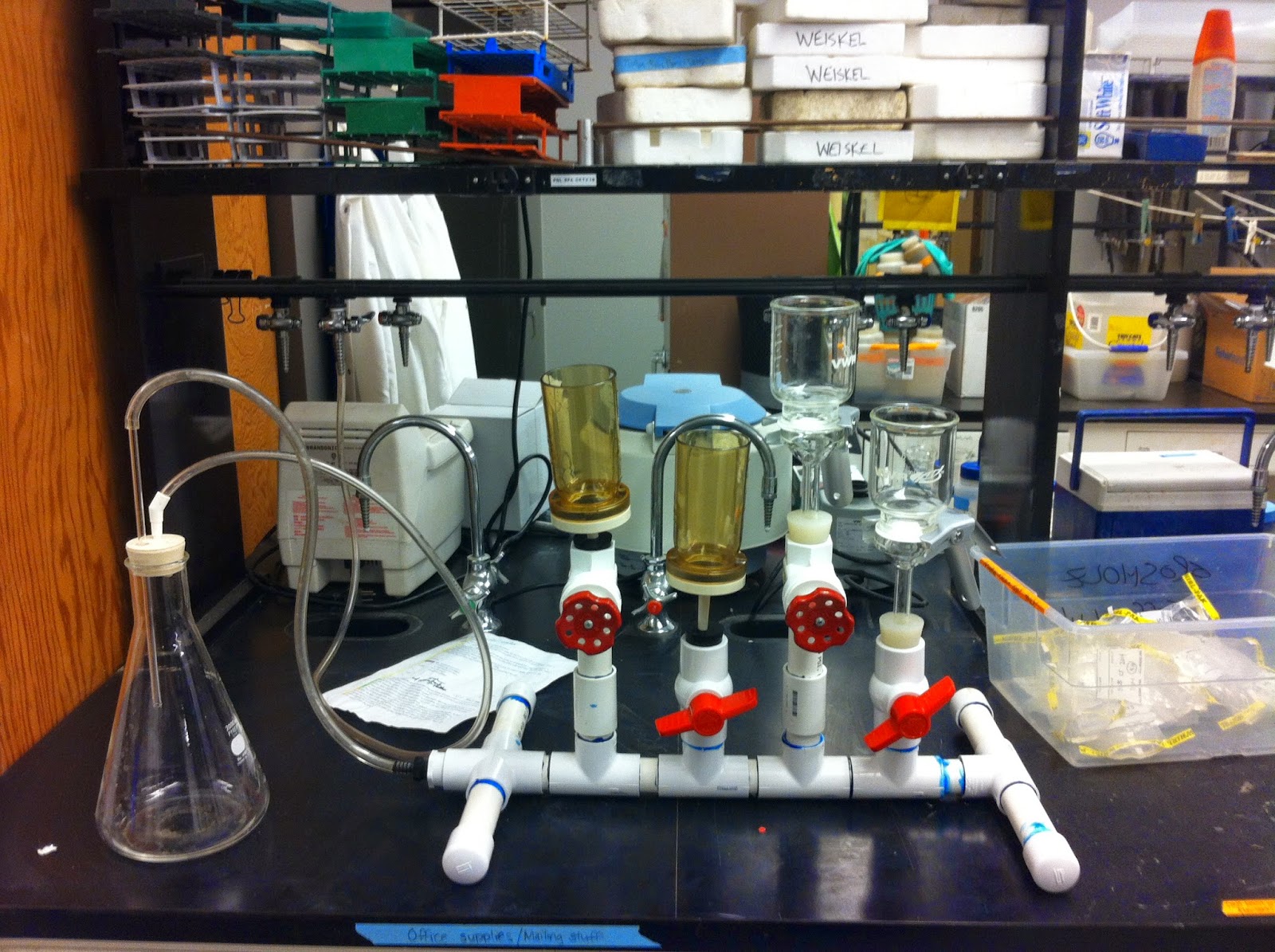

|

| Beakers and stuff, like a real scientist. |

No comments:

Post a Comment